“This highway, may it serve to bring Canadians closer together. May it bring to all Canadians a renewed determination to individually do their part to make this nation greater and greater still, worthy of the destiny that the fathers of confederation had expected when, through their act of faith, they made it possible. And above all, I express the hope and the prayer today that this highway will always serve the cause of peace, that it will never hear the marching tramp of warlike feet.”

–Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, September 3, 1962

We wonder what Diefenbaker would say if he could see the Trans-Canada Highway in B.C. now, more than 50 years after he officially packed down the last small patch of pavement at Rogers Pass in front of about 3,000 eager travellers.

We wonder what Diefenbaker would say if he could see the Trans-Canada Highway in B.C. now, more than 50 years after he officially packed down the last small patch of pavement at Rogers Pass in front of about 3,000 eager travellers.

Undoubtedly, he’d be relieved to discover the only battles along the 8,000-kilometre route have been fought against natural elements such as avalanches, floods and slides. But to show just how far B.C. Highway 1 has come, let’s take a look way back at the evolution of a few of the route’s most compelling features.

Malahat Drive [Google map]

Some Vancouver Islanders once thought building a road on the east side of the Malahat mountain impossible; but not Major James MacFarlane, who was compelled to survey a direct route to Victoria from his farm in Cobble Hill. Before the first edition of Malahat Drive was built, travellers were forced to make an inconvenient three-day inland journey. Fed up with taking the long way to Victoria markets, MacFarlane successfully lobbied the government to build the modern route and, in 1911, the first automobile travelled the narrow two-lane gravel road over the 350-metre summit. It’s said MacFarlane was actually the first person to cross, with a team of horses.

The roadside view of Saanich Inlet was stunning right from the get-go, but, as you can imagine, driver safety in those days was lacking. Rock and mud slides posed a threat and the mountain road originally had no guard rails protecting its tight curves. A series of safety enhancements over the years have drastically improved the Malahat. The looming rock slopes have been stabilized to prevent slides and concrete median barriers are being added. More than 75 per cent of the Malahat corridor will be separated with median barrier when the project is completed. On average, about 22,000 vehicles travel the 20-kilometre long Malahat every day.

Port Mann Bridge [Google map]

Although the Trans-Canada Highway was officially opened in 1962, it wasn’t fully completed until 1971. One such belated section was the Port Mann Bridge connecting Coquitlam and Surrey, which opened in 1964. At the time, the steel tied arch bridge over the Fraser River had four lanes; a fifth carpool lane was added about 10 years ago. While the original Port Mann Bridge was built when the area’s population was about 800,000, it now feels tread from that many vehicles per week. Queue the Port Mann/Highway 1 Improvement Project.

The new 10-lane Port Mann Bridge is the longest cable-supported bridge in North America (two kilometres) and one of the widest bridges in the world (65 metres). Simply put, it’s a massive piece of construction.

Kicking Horse Canyon [Google map]

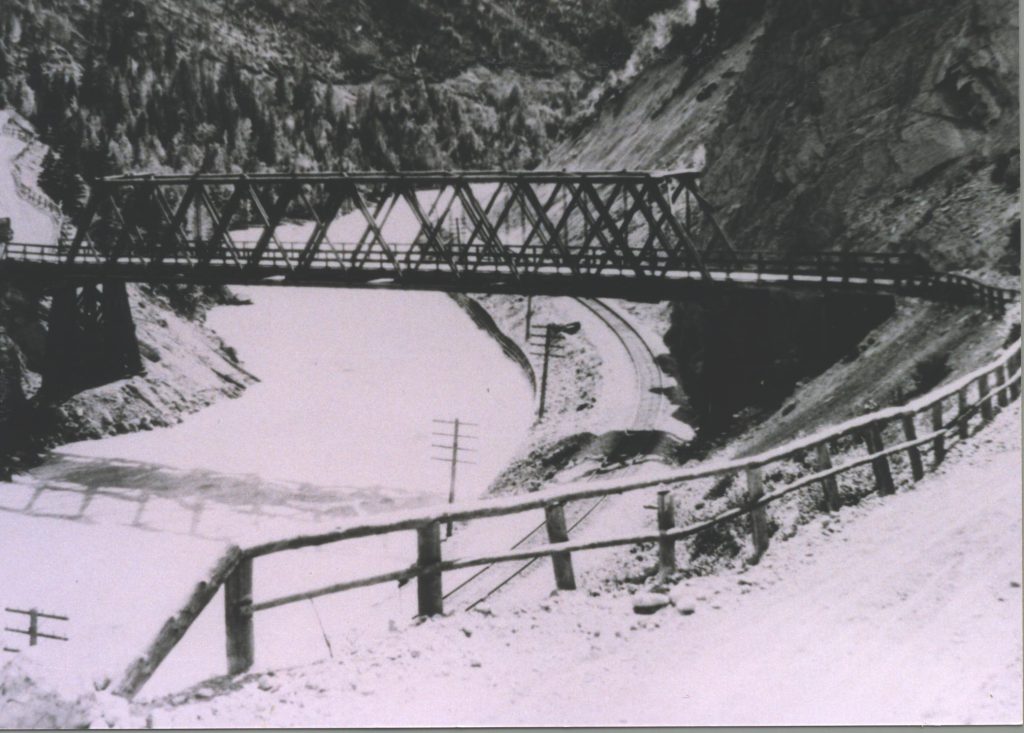

Between Golden and the Alberta border sits Kicking Horse Canyon, the most easterly section of B.C.’s Trans-Canada Highway. It got its name from Palliser Expedition members, who surveyed the pass about 150 years ago, after one unfortunate member got kicked in the chest by a disgruntled pack horse. The original highway was built in the 1950s: two lanes carving between looming rock faces and steep drop-offs, winding through hairpin turns, and two narrow crossings over the Kicking Horse River.

Upgrading this 26-kilometre section of the Trans-Canada Highway was vital for keeping drivers safe and sustaining B.C. as the country’s gateway to the Asia-Pacific market. The first three phases of the project focused on replacing the two major river crossings, cycling improvements, electronic message signs, wildlife fencing and crossings, median barriers and four-lane expansion. Yoho Bridge and Park Bridge were rebuilt and the approaching roadways were realigned. Watch this construction time lapse video to see Park Bridge rise 90 metres from the canyon floor in just two minutes. It’s truly amazing.

Phase four will upgrade more than four kilometeres through the most challenging section of the canyon. Combined with the 1962 creation of the Trans-Canada link through Rogers Pass, the improved Kicking Horse Canyon route reduces travel time between Vancouver and Field, on the Alberta border, to about 10 hours.

It’s safe to say Diefenbaker would be impressed by the colossal improvements to B.C.’s portion of the Trans-Canada Highway. When the province started construction in the early part of the 20th century, it was faced with some of the most challenging terrain in the country. We have since developed innovative ways to support safe journeys and open Canada to the Pacific and beyond. Instead of fearing the “marching tramp of warlike feet,” we encourage international trade and invite the world to explore our landscapes. Perhaps best of all, the Trans-Canada Highway continues to bring Canadians together from coast to coast.

Join the discussion