BC’s historic landslides are large-scale tracts of land that move over time, impacting communities, roads and bridges.

They may “creep” as slowly as a few millimetres a day or year. Then, they can “reawaken” and move downward more rapidly and dramatically, like areas in the Cariboo – burying or washing out roads, at times cutting off communities.

What can’t be seen below the ground, is what’s at play. Geologic materials such as clay, silt, sand, gravel and even rock can collapse due to changes in groundwater.

The movement over time of these slides is what distinguishes them from more “typical” short-term, instantaneous slide events like debris flows, or rock falls, which typically occur due to rain events, freeze-thaw cycles or warming temperatures. (Though both water and temperature can re-awaken a historic slide.)

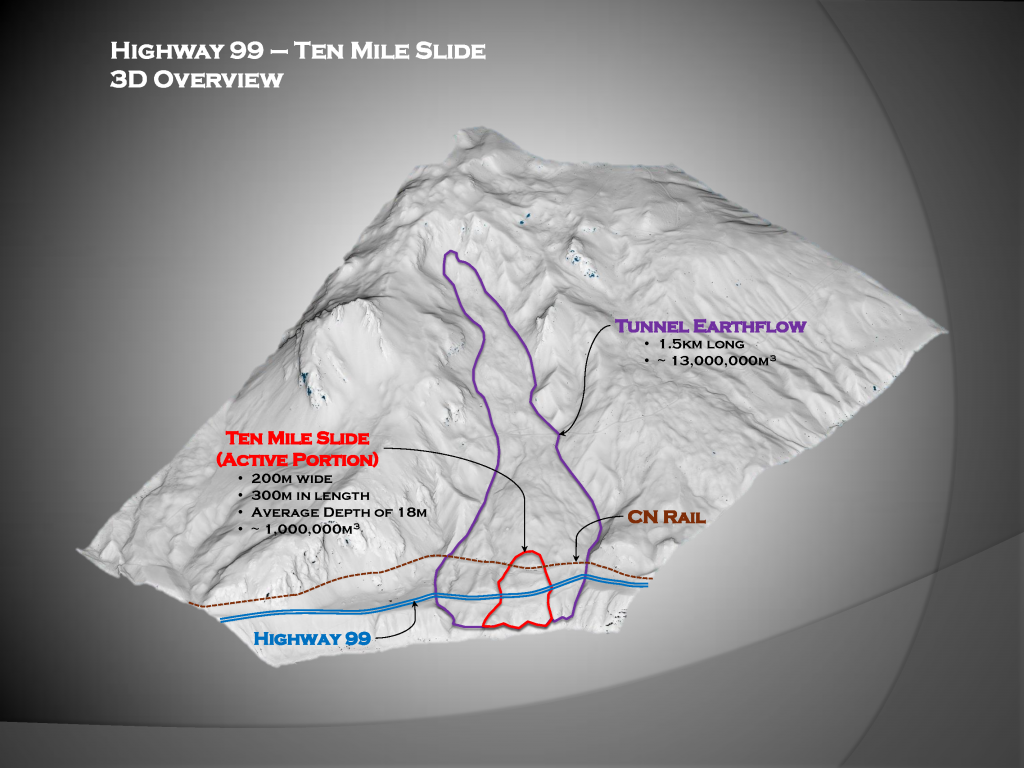

Historic slides can be massive, complex and extremely challenging and expensive to manage and stabilize. For example, Ten-Mile Slide northeast of Lillooet is 200 metres wide at Highway 99 and 300 metres long. About 750,000 cubic metres in size, it’s part of a large inactive “tunnel earthflow.”

What to Do with Historic Slides?

Historic slides can have a major impact on the people who live and travel an area. So, what can be done to manage these situations?

When it comes to solutions for highways, roads and bridges that have been affected, we look at numerous factors like engineering, construction, environment, community and Indigenous considerations to ensure that our transportation infrastructure is safe and reliable for motorists.

Generally, we have three approaches:

- Monitor and make improvements, while inspecting regularly to assess changes, patterns and hazard levels, and conducting maintenance as required.

- Local realignment, or simple stabilization methods such as removing water from the slide, taking away some materials (e.g. rock, sand, clay) from the slide’s “crest” (highest point) to reduce the slide’s driving force, or placing reinforcing materials at the slide’s “toe” (bottom area) to resist the slide’s force.

- Provide permanent alternative access, or stabilize the slide with a structural solution which may include retaining walls and/or soil anchors.

Each slide is different, each scenario is different. West Fraser Road, south of Quesnel, which washed out in five places in 2018, is one location where moving the road to a more stable area was the best option. Construction work began in 2021, on a new bridge and a 5.6-kilometre stretch of road. In 2023, work was completed on the two-lane bridge over Narcosli Creek, and two-lane section of road that bypasses the active slide areas.

How decisions are reached is complex, and multiple aspects are examined for each situation, including economic activity, travel time, community connectivity, environmental impacts and costs (to name only a few). We have identified some below:

Recognizing the impacts of changing weather patterns, we have continued to evolve our strategy. Our design engineers and consultants are considering how future climate events will affect infrastructure and what can be done to make our roads and bridges more resilient, so they remain reliable and open.

Some works include upsizing culverts, building bridges where culverts are no longer suitable, redesigning drainage channels for future flow and armouring of water channels. This approach considers climate adaptation is over the life of our infrastructure. Additionally, we’re incorporating design stabilization approaches that are more resilient to the impacts of climate change.

Following are a few case studies of how we’ve handled historic slides.

Cariboo Road Recovery Projects

Changing weather patterns have hit the Cariboo particularly hard in recent years, contributing to hundreds of landslides and road washouts in areas near Williams Lake and Quesnel. To address the damage and resulting transportation impacts, the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure is undertaking the Cariboo Road Recovery Projects. These projects aim to restore access where feasible, benefiting tens of thousands of people who use the affected roads and highways.

The program is designing and building transportation infrastructure that is resilient and dependable for communities and road users in the long term. To date, five projects are proceeding to construction.

Geotechnical investigations and engineering analysis are underway for four projects. Each project is being carefully reviewed to ensure climate resiliency is considered in its final design.

Project Feature: Highway 97 at Cottonwood Hill

One of the projects currently under construction is Highway 97 at Cottonwood Hill.

In 2020, a historic 8.8-hectare landslide reactivated, causing significant ground movement that impacted the highway. While the affected section remained open, the project team conducted investigations and continuously monitored the slide’s impacts. With minimal additional movement detected, the team proceeded with riverbank erosion protection works in fall 2023, including groyne installations in the Cottonwood River, to prevent further destabilization and reduce the risk of future slides.

Phase 2 of the project began in July 2024 and focused on the reconstruction of a 500-metre section of Highway 97 and the removal of material from the top of the slope to decrease the likelihood of future movement. The third and final phase, involving slope stabilization beneath this stretch of highway, is set to begin in 2025 and continue through 2026.

This project showcases a multi-phase approach that goes beyond just fixing the road. By tackling riverbank protection, road reconstruction, and slope stabilization, the team is addressing all key aspects of the landslide to promote long-term stability and safety for the entire area.

Project Feature: Quesnel-Hydraulic Road

Quesnel-Hydraulic Road is an example of how the Cariboo Road Recovery Project team is using high-tech solutions to monitor impacted areas and mitigate landslide risks while long-term solutions are developed.

In 2020, an intense period of rain reactivated a series of historic landslides totalling 13 hectares, leading to the closure of Quesnel-Hydraulic Road. To maintain access, an alternative route was established along French Road, a former Forest Service Road.

By spring 2023, crews focused on additional interim works to reinforce the embankment by installing riprap along a portion of the west riverbank beneath Quesnel-Hydraulic Road. This was designed to protect the area from potential erosion caused by the Quesnel River. High-tech monitoring equipment was installed throughout the project area to provide early warnings of any additional ground movement.

In July 2024, the monitoring equipment detected changes in the road’s condition, prompting emergency works to address issues related to slide movement. These efforts included crack repairs and stabilization measures to ensure the road’s safety.

Through a combination of interim measures and advanced technology, the project team has successfully maintained access and ensured the safety of the area. This project demonstrates the team’s commitment to using modern solutions to address the challenges posed by historic landslides.

Additional Key Projects in the Cariboo Recovery Effort

In addition to these highlighted efforts, several other critical projects are advancing as part of the Cariboo Road Recovery Program:

- The Highway 20 at Hodgson/Dog Creek Road project has completed its first phase of surface water management and continues with geotechnical monitoring. Further investigations and multi-jurisdictional collaboration are planned to develop a long-term solution.

- The Blackwater Road at Knickerbocker Slide project will commence groundwater depressurization in fall 2024, followed by road reconstruction and erosion control, with completion expected by 2026.

- The Kersley-Dale Landing Road project is progressing, with construction of a new alignment anticipated to begin as early as fall 2024.

- At Highway 97 at Cuisson Creek, safety upgrades are already underway, including shoulder widening and barrier installation to address erosion risks.

- Soda Creek-Macalister Road will undergo significant regrading and drainage improvements in 2025 to restore safe public access, with the Xat’sull First Nation playing a key role in project delivery.

Each of these projects is designed to address the unique challenges posed by reactivated historic landslides and changing weather patterns.

Each of the Cariboo Road Recovery Projects, shaped by reactivated historic landslides and changing weather patterns, presents distinct challenges to their multidisciplinary teams that require tailored solutions. These solutions draw on proven engineering expertise, community feedback, and scientific data to ensure both long-term safety and climate resilience. The program will continue to keep communities and stakeholders informed with regular progress updates and images on project webpages as the program advances. Looking ahead, the program’s next steps will remain focused on designing and building transportation infrastructure that is resilient and dependable for communities and road users over the long term.

Ten Mile Slide – Soil Anchor Stabilization

Ten Mile Slide, located within the Xaxli’p First Nation community, northeast of Lillooet on Highway 99, is a highly dynamic slide. It has been described as ancient, and since 1988, the slide’s average movement has ranged from 10 millimetres a day to up to 50 millimetres a day.

For a few years, slide activity required the stretch to be limited to 24/7 single-lane alternating traffic, commercial vehicle load restrictions were required, and considerable road maintenance was needed.

This portion of Highway 99 is the primary connector between Lillooet, Xaxli’p and Kamloops, and vital to local communities and the regional economy. The Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure and Xaxli’p worked collaboratively over time to reach a long-term solution to the slide’s ongoing movement, and engineering consultants and construction contactors performed extensive analysis and extraordinary works.

In October 2021, structural stabilization concluded. The final solution was 276 soil anchors installed through individual 2.5 metre square concrete blocks above Highway 99. Below the highway, there is a tied back concrete pile retaining wall composed of 148 large-diameter piles with 125 tie-back anchors (closeup photos here). Geotechnical Engineer Tom Kneale describes the lower structure, “Like a whole bunch of football players standing at the bottom of the hill, holding the slide back.”

This section of highway was also re-aligned and restored to two lanes. In the short-term, the road remains a gravel surface until the site settles, which is anticipated to be in late 2023.

Seeking Solutions in Shifting Circumstances

Managing historic slides takes a great deal of analysis to assess the slide’s behaviour and then, with expert information and community input, to choose the best option. Like the slide and the earth itself, things shift and change, just as our climate is changing. Our commitment is to keep you moving safely through it all.

We hope you’ve found this explanation of historic slides, their impacts and how we manage them, to be informative and interesting. For other geotechnical topics see these blogs:

- Dig into the Work of a Geotechnical Engineer

- What Happens After a Rock Hits a BC Highway

- Our Geoscientists Dig Deep to Keep BC Highways Moving Safely

- What Happens After a Washout Hits a Highway

- Three Ways We are Working to Protect BC Highways from Climate Change

Thanks to BCG Engineering, whose project summary we drew on, for the section on Ten-Mile Slide.

Is there a publicly accessible database of mapped or suspected areas of soil instability in the province?

I was with BCFS in Lytton in 1975 and worked on the forest access road between Drynock East and West Overheads there is a large area of instability there with survey points and monitoring wells I would be very interested in accessing information on how it is doing.

Hi Ian – we just did a quick google search and found this link for you: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/mineral-exploration-mining/british-columbia-geological-survey/geology/bcdigitalgeology

Hopefully it works for you. Safe travels.