Highlighting BC highway history is important – and that doesn’t just mean shining a light on the gleaming parts of our past – it also includes bringing light to those darker parts of our history that we must learn from so we can move forward. Knowing how and why we experienced past successes and failures help us plot a better course for the future, which is why we are humbled and proud to have unveiled eight special Stop of Interest signs, commemorating the 75th anniversary of Japanese Canadian internment during the Second World War.

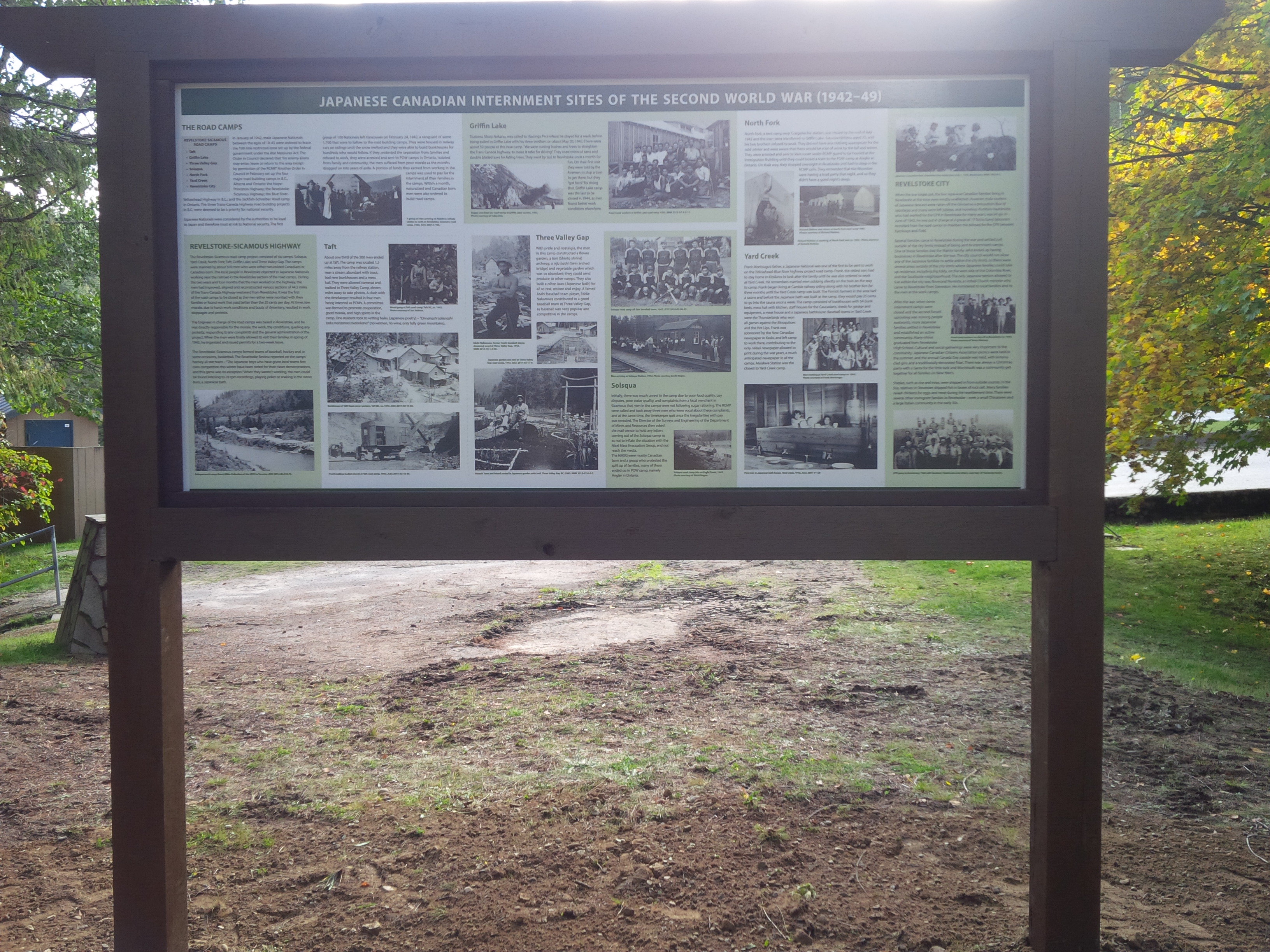

Working with the Japanese Legacy Committee, it was decided to highlight this piece of history with a series of eight interpretive signs and, since October 2017, they have been installed along our highways to recognize sites of historical significance for Japanese (and all) Canadians:

• Tashme Internment Camp – Highway 3

• East Lillooet Self Supporting Internment Camp – Highway 12

• New Denver Internment Camp – Highway 6

• Kaslo Internment Camp – Highway 31

• Slocan City Internment Camp – Highway 6

• Greenwood Internment Camp – Highway 3

• Hope-Princeton Road Camp – Highway 3

• Revelstoke-Sicamous Road Camp – Highway 1

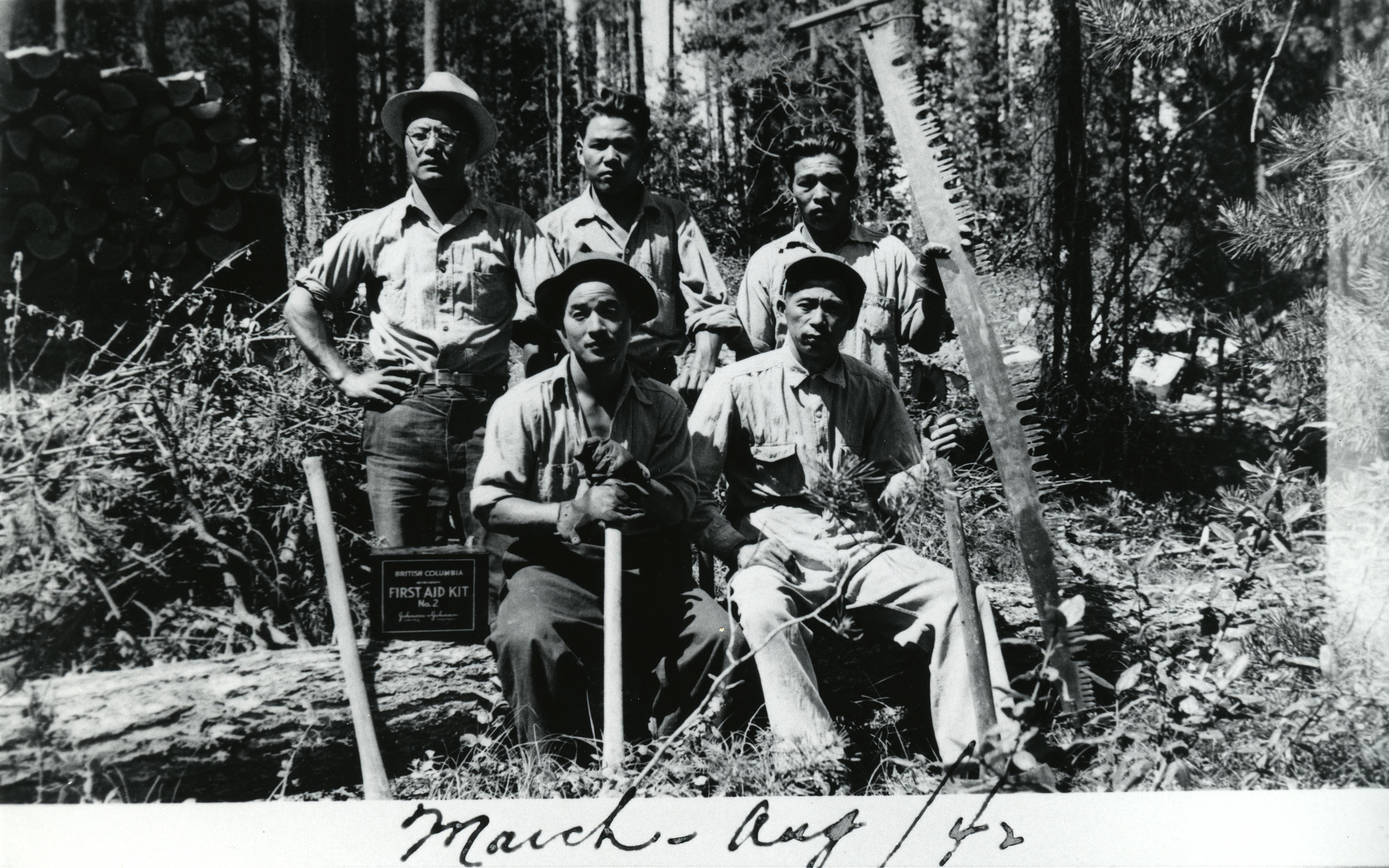

The final sign, unveiled on Sept 28th, 2018, is located at the Rutherford Beach rest area on Highway 1. It helps share the history of the Revelstoke-Sicamous road camp and the Japanese Canadian men who were forcibly sent to work there to build the Trans-Canada Highway during the Second World War.

In 2019, we installed a Stop of Interest sign along Highway 5, north of Blue River at the Thunder River Rest Area, to recognize Japanese Canadians sent to road camps in that area.

What Happened to the Japanese Canadian Community During World War II

In 1942, after Canada declared war with Japan, more than 21,000 Japanese Canadians and Canadians of Japanese ancestry were registered as “enemy aliens,” despite the fact that about half of them were naturalized Canadians or had been born in Canada. Most of these people lived in British Columbia.

The government of the day created a 100-mile (160 km) “Protected Area” along the west coast of B.C. and it was deemed to be a matter of national security that all persons of Japanese ancestry be removed from that area. The War Measures Act legislated that men between the ages of 18 and 45 would be the first to be relocated. They were sent to forced-labour road building camps in the interior of the province, where they worked for less than 25 cents per day, often in harsh conditions.

When men protested being separated from their families, they were arrested and sent to Prisoner of War camps. Women and children were left to fend for themselves as they were processed for transfer to internment camps in the interior of BC, and other locations east of the Rocky Mountains.

Lasting Impacts Post War

After the end of the war in 1945, the camps began to empty; however, many people were not permitted to, or did not want to, return to their former communities on BC’s coast because of ongoing exclusionist policies implemented by the provincial and federal governments.

It wasn’t until 1949, when the racially biased restrictive powers of the War Measures Act were rescinded, that Japanese Canadians were free to vote, live where they wanted, and to come and go as they wished. Some returned to the coast of BC, and many returned to fishing communities such as Steveston to rebuild the lives and livelihoods that had been so forcefully and traumatically taken away in 1942.

Rebuilding a sense of trust and acceptance took years but, during the 1970s there was a rebirth of Japanese culture and ethnic pride across Canada, which renewed a sense of community and strongly influenced the 1988 redress and formal apology by the federal government for all wrongs committed against Japanese Canadians during World War II.

In 2012, the Province of British Columbia extended a formal apology to Japanese-Canadians interned during the Second World War. The eight interpretive signs erected across the province are small symbols acknowledging these terrible wrongdoings, but we hope they spark important conversations about basic human rights with younger generations of British Columbians who have the terrible experience of war.

Moving Forward

“I am extremely grateful to see the completion of this highway legacy sign project,” said Laura Saimoto, chair of the Japanese Canadian Legacy Project Committee. “With the installation of these signs, we are honouring those 22,000 Japanese Canadians who were wrongfully uprooted from their homes and educating future generations about our history.”

On your next highway road trip across BC, we encourage you to stop to remember this piece of our history.

Do you have any questions about this, or anything else we do here at the Ministry of Transportation and infrastructure? Let us know in the comments below.

My Grandfather was a guard at the Sicamous Internment camp , and was much liked by the prisoners. I have in my possession a stick that was beautifully carved by one and given to him as a gift. He served in W.W.1 and was at Vimy Ridge. His name was James S. Moodie.

Thank you for sharing this story with us, Gary! We love hearing them. Safe travels.

Looking for a beautiful friend , Nancy Amano, who went to Lucerne High School, New Denver with me in 1956,1957.

I have never forgotten her.

If previously posted can it please be posted again.

Hi Sandra – we hope you find her!

Hi there 🙂 Just a note for your readers of this wonderful article. I’m following up the previous comment by my colleague, Mika. It appears we have a lost and forgotten sign, possibly caused by the changeover in government not too long ago. Although forgotten the sign has been wonderfully cared for, and is waiting for acknowledgement. The editor is correct that there was an interpretive sign at Mount Robson created as part of a B.C. Parks initiative. However, there was a second sign installed at Mount Robson that same year. The second sign was created by the B.C. Ministry of Transportation and is a large brass Stop of Interest sign. This sign was initiated by the Japanese Canadian Legacy Project Committee and was cast by the BC Ministry of Transportation in 2017. It was delivered to Mount Robson in 2018, and ended up being installed by the Mt. Robson Park manager at the edge of the MOT parking lot… with an amazing view of Mount Robson behind it! As for me, I’m a researcher who acted as a heritage consultant for the text of this Stop of Interest sign. The party that I worked with at that stage was the Japanese Canadian Legacy Project Committee. I also helped with the process of determining where the sign should be placed, and the decision was that Mount Robson would be great. However, because the Legacy Committee had so much to do and the area was so remote it was difficult for them to organize a ceremony for the Mt. Robson sign. When the members of the National Association of Japanese Canadians went to Mt. Robson to dedicate the BC Parks sign, we helped facilitate the installation of the MOT sign, because the sign was not yet in the ground. The sign is beautiful! Hopefully we won’t forget about it. Although it must feel a bit odd for the Legacy Project committee members to have one of their stop of interest signs happen all by itself, the sign is a result of the Committee’s hard work and should be placed among the others where it was intended to be. Like the other two highway project signs, this sign commemorates the Japanese Canadian forced labour in 1942 and the workers’ efforts in building parts of Highway 16 and Highway 5. It was the first project to which Japanese labourers were sent. More that fifteen hundred men of Japanese descent were sent there. Although there was no ceremony for this particular sign, I hope there will be one day and that I can be a part of it. Thanks for all your work, and I hope that this is helpful information.

Good morning Leanne and thank you so much for this message and for bringing this to our attention. Our Stop of Interest team is looking into this further and we will let you know what we hear from them.

Interesting article and an important reminder of our history. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks for reading, James.

It is a nice to acknowledge the history and wrongdoings. I am still amazed how many people of Japanese descent that have spoken with who’s family’s were directly impacted by this dark part of Canadian history.

The Yellowhead-Blue River road camps signage is also up at Mount Robson (the place where Japanese nationals were sent beginning in February 1942, before the other road projects). The Legacy Project seems to omit this because this signage project was started earlier, but I believe they are still a part of this sign project too (there was a speech given at the opening, although the representative could not be present). Please include it on your list. The sign went up in late June 2018. A stop of interest sign is also there too.

Hello Mika,

The Yellowhead-Blue River sign was part of a BC Parks initiative not our project, which only included the eight interpretive signs. We are happy to talk with you directly if you would like to discuss further!